Whether by protesting against oppression and violence, criticizing political affairs through satire, or helping to negotiate loss, music is unique in its potential for social transformation. For this reason, music is one of the branches of art that we want to highlight as part of our Make Art Not War project area. At the Cultures of Resistance Network, we draw inspiration from musical practices—whether cathartic, communicative, subversive, or all three at once—that carry their own strategies of resistance. Music is not only a means of expression that sublimates the experience of daily life but a critical form of dialogue by which citizens participate in public life. The act of performance itself affirms the right to construct a cultural space in opposition to conditions of cultural hegemony and political and military oppression.

This page points to some highlights in the past century of musical resistance around the globe, providing a brief introduction to the kinds of art that inspire the work of the Cultures of Resistance Network‘s Make Art Not War project area. On separate pages, we take a more in-depth look at dissident music past and present in four Middle Eastern countries. Follow the links below to learn about the legacies of musical resistance in:

Background: A Century of Musical Resistance

Scores of twentieth-century dissidents have turned to song and symphony as vehicles to mobilize against censorship, fascism, and racism. Decades after state censorship of his Lady Macbeth opera, Dmitri Shostakovich risked arrest with his audacious setting of Yevtushenko’s poem “Babi Yar” in his Symphony No. 13, which commemorated the Nazi massacre of 200,000 Jews near Kiev during WWII. “Look Out, Verwoerd” by South African singer/activist Vuyisile Mini, offered an ominous, albeit melodic warning to the first engineer of Apartheid, Hendrik Verwoerd, while inspiring countless South Africans to organize for their rights as citizens in 1950’s South Africa. Bob Marley, in addition to being one of the world’s all-time greatest songwriters, was also a vocal advocate of peace and black power in the political tumult of 1970’s Jamaica.

In an increasingly globalized world, artists borrow and exchange musical styles and genres as they express affinity between conditions of marginalization and oppression. Basque nationalists Negu Gorriak syncretize punk, ska, reggae, and rai styles into their militant protest music, and moreover, they attribute their breakdancing, graffiti writing, and rapping to the influence of Public Enemy. Reggaeton’s dem- bow rhythm is a mash-up of Brooklyn hiphop and Jamaican dancehall that blasted out of San Juan’s housing projects in the 1990s and today galvanizes U.S. activists for immigrant rights in the States. While some may lament the commodification of these styles into idiomatic cliches, the distribution of LPs, cassettes, CDs, satellite and online media helps facilitate solidarity between fans and producers on a global scale.

bow rhythm is a mash-up of Brooklyn hiphop and Jamaican dancehall that blasted out of San Juan’s housing projects in the 1990s and today galvanizes U.S. activists for immigrant rights in the States. While some may lament the commodification of these styles into idiomatic cliches, the distribution of LPs, cassettes, CDs, satellite and online media helps facilitate solidarity between fans and producers on a global scale.

Antiwar solidarity may take the form of protest songs like Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War,” Chava Alberstein’s “Chad Gadya,” and the Dixie Chick’s album “The Long Way Around,” or as reception among audiences, such as the current popularity of Megadeth’s “Holy Wars” among college-age youth in Cairo. Antiwar resistance may also be the bold expression of alternate and creative ways of life under conditions of military aggression.

Antiwar solidarity may take the form of protest songs like Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War,” Chava Alberstein’s “Chad Gadya,” and the Dixie Chick’s album “The Long Way Around,” or as reception among audiences, such as the current popularity of Megadeth’s “Holy Wars” among college-age youth in Cairo. Antiwar resistance may also be the bold expression of alternate and creative ways of life under conditions of military aggression.

Music alone has rarely sufficed to prevent war, but it has almost always played an important role in helping people overcome the suffering brought by conflict, providing a sense of normality, community, and hope in settings where these have been all but destroyed by bombs. The photograph to the left (click for a larger version) shows Vedran Smailović,  known as the cellist of Sarajevo, playing in his country’s largely destroyed National Library at the height of the siege of Sarajevo in 1992, in an act of resilience that has become iconic of the power of music to triumph over the ravages of war. But this is only one example of the ways that music can help people survive, heal, and rebuild from even the grisliest of conflicts; elsewhere in the Balkans, for example, music projects ranging from rock bands to choral ensembles have helped people recover from years of bloodshed and ethnic cleansing.

known as the cellist of Sarajevo, playing in his country’s largely destroyed National Library at the height of the siege of Sarajevo in 1992, in an act of resilience that has become iconic of the power of music to triumph over the ravages of war. But this is only one example of the ways that music can help people survive, heal, and rebuild from even the grisliest of conflicts; elsewhere in the Balkans, for example, music projects ranging from rock bands to choral ensembles have helped people recover from years of bloodshed and ethnic cleansing.

The Cultures of Resistance Network‘s Make Art Not War project area aims to give exposure to audio and visual art that is created and performed by those immediately affected by political and military oppression who are committed to using their art as a force for justice. As part of our ongoing pursuit of dissident musicians and musical traditions around the world, we’ve done a more in-depth study of musical resistance traditions in four Middle Eastern countries: follow the links to check out our country pages on Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, and Palestine. Or, to learn about more great artists channeling the spirit of resistance in the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, and the United States today, return to the Make Art Not War project area menu.

Iran: Histories of Musical Resistance

The cultural politics of music in Iran during the twentieth century are narrated in part by the shifting dynamics of modern Iranian politics and society. From the decline of the Qajar Dynasty (1781-1925) to the height of the Pahlavi Dynasty (1925-79), musicians gained autonomy and independence as they rejected the bonds of private patronage and began to perform for broader audiences, not all of whom were connoisseurs of classical Persian music. Cultural emancipation did not always occur sans injury—when composer and musician Darvish Khan performed at a private party without the consent of his patron, the Qajar prince threatened to sever off Khan’s hands as punishment. Khan sought refuge in the English embassy at Tehran and his subsequent enfranchisement from the prince came to symbolize, for later generations of artists, gradual processes of cultural democratization in Iran.

In the 1950s, Iranian pop and jazz flourished in Tehran’s cafes and cabarets. By the latter years of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s regime, popular music occupied over 90% of radio and television music programs. Some artists blended Western popular music and instruments with Iranian tasnif, a vocal genre that was introduced by Aref in fin-de-siecle Iran as a vehicle for political commentary. Prominent singers include cult favorite Googoosh, Dariush, and Ebi. Some artists grew increasingly discontent with what they viewed as the Shah’s endorsement of popular music and the over-democratization of culture, such as Habib Soma’i, who slapped the director of Radio Tehran in protest over the station’s efforts to expand to a larger public.

In the 1950s, Iranian pop and jazz flourished in Tehran’s cafes and cabarets. By the latter years of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s regime, popular music occupied over 90% of radio and television music programs. Some artists blended Western popular music and instruments with Iranian tasnif, a vocal genre that was introduced by Aref in fin-de-siecle Iran as a vehicle for political commentary. Prominent singers include cult favorite Googoosh, Dariush, and Ebi. Some artists grew increasingly discontent with what they viewed as the Shah’s endorsement of popular music and the over-democratization of culture, such as Habib Soma’i, who slapped the director of Radio Tehran in protest over the station’s efforts to expand to a larger public.

The 1979 Revolution: Resisting Cultural Hegemony

Following the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini condemned all forms of music, other than classical and traditional Persian music, as “influenced by the culture of the foreigners.” In his first three or four years, Khomeini pursued an aggressive cultural policy that forbade women from singing in public, banned the payment of musicians under shar’ia (Islamic law), and shut down cafes and cabarets. He insisted on the need for a “cultural reconstruction,” pointing out that as “the road to reform in a country goes through its culture, so one has to start out with a cultural reform.” Linking Russian and English territorial pursuits in the 19th century with American cultural influence in the twentieth century – an influence that was embraced by Shah Pahlavi – Khomeini condoned the national Radio and TV broadcasting corporation as the product of a “colonized culture” that produces “colonized youth.”

Khomeini’s urge to establish an Islamic social order that excludes particular musical practices is driven by two overlapping claims: a resistance to cultural hegemony from the West and an interpretation of the Hadith (the tradition of the Prophet Mohammed) that is situated in a centuries-old debate in the Middle East and North Africa. Referred to as the sama’ controversy, this seeks to interpret the role and definition of music in an Islamic society. (In short, the sama’ controversy questions the moral permissibility of forms of music – Quranic cantillation, pilgrimage and praise songs, jazz and dance music, et al. – through taxonomies that differentiate these forms through claims to legitimacy based on Islamic principles dictated by the Quran and interpreted in hadith.) According to Khomeini’s rendition of a section of the Hadith, “listening to music leads to discord (nefâq)… music is said to unsettle the soul, to lead people to indulge in the pure sensuality of the physical experience of their bodies… the only kind of music that can lead to transcendence is the one that is based both on science and lofty ideas and on the virtuous feelings of mankind… one that binds a cultural and artistic community by the reinforcement of a moral and national character.” The contradictory nature of permitting some musical practices, such as traditional and classical Persian radif, and not others, is not only politicized by cultural colonialism but a product of defining music in contradistinction to morally impermissible ways of being.

Since Khomeini’s death in 1989, cultural policy has heeled the ebb and flow of the interpretation of shari’a by Iranian presidents. Following the end of the Iran-Iraq war in 1989, President Rafsanjani began to relax some restrictions on public life in Iran. The government’s endorsement of rock, pop and other forms of popular music – nostalgic ballads and love songs set to electric guitar, keyboards, bass and drums – was likely motivated by market competition with cultural production among Iranian expatriates living in Los Angeles. When Khatami was elected in 1997 as the first reformist president, he encouraged economic and cultural liberalisation through which artistic and intellectual life in Iran flourished to an unprecedented degree. Since his 2005 victory, current President Ahmadinejad has dampened this cultural thaw and reproduced an environment that echoes many of Khomeini’s orthodox interpretations of Islamist law and reform.

For more information on the status of cultural production in Iran today, see the 2006 report “Unveiled: Art and Censorship in Iran” from Article 19, a human rights organization dedicated to the freedom of expression and freedom of information worldwide.

“Sawt al-Mar’a ‘Awra” / “The Voice of a Woman is a Shameful Thing”

The prohibition against public performances given by women is similarly ensconced in the relative opposition of halal (permissible) and haram (impermissible). Woman’s bodies are sexualized by certain Islamist constructions of gender such that a feminine voice may seduce the listener and a female body, dancing or otherwise, may evoke tempting images. While women are hardly excluded from musical life in Iran – the number of female classical musicians has increased significantly since 1988, particularly as composers and instrumentalists in the National Symphony Orchestra – the following women artists stand out as exceptional citizens in a society draped with a chador.

Qamar al-Moluk Vazirizadeh (1905-59)

The first Iranian woman to sing in public, she gave her 1924 concert at Tehran’s Grand Hotel to an audience that numbered in the thousands. Later that year she recorded “March of the Public” (written by Aref in memory of Eshqi, a patriot poet) but the government confiscated this and other recordings.

Parisa

Trained in dastgah and radif, Parisa is beloved among Iran’s classical singers for her renditions of poems by Rumi, Hafez and Sa’adi. After her performance career was abruptly interrupted in 1979 by the Iranian Revolution, she began to work with female students through the Center of Preservation and Dissemination of Music, where she taught from 1980 – 1995. Though still barred from public performance in Iran, Parisa regularly tours outside of Iran with tar virtuoso, Dariush Talai.

Sima Bina

In 1994, Sima Bina became the first Iranian woman singer to tour Europe and the US since the Revolution. She collects and performs folksongs from the Khorasan region in the northeast and Lorestan in the southwest, in addition to the classical repertoire.

Sima Bina. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Arian

This nine-piece band pioneered the first mixed gender pop group in Iran in 1998. Recognized as the group that opened up doors for other mixed gender ensembles, they are now officially sanctioned by Ershad (Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance) with permission to perform and publish their music in Iran, and to regularly tour outside of the Middle East.

Iran Underground: Voices of Youth

Despite the current government’s hyperactive censorship and banning policies, the new face of Iran’s black market music and video is sited on the web, particularly among the 70% of Iran’s population who are under 30 years old. Iran is the fourth most active country with more than 75,000 blogs in Farsi posted by Iranians worldwide, music downloads are also available for new and old musicians like Vigen Derderian and Dariush Shahriari. A number of the musicians profiled below are particularly well-known as those who broke ground on the web as an outlet for music production that is denied official authorization by Ershad.

For the latest in Iran, check out Zirzamin, an online zine for underground Iranian music scenes with reviews, event listings and more.

Babak Khiavchi

Foremost producer of Studio Bam, the legendary production house that triggered many of Tehran’s cutting-edge bands, he offers an interview about life in Canada and the current relations between underground Iranian scenes and Western audiences.

O-Hum

Widely regarded as Tehran’s pioneers in underground rock, this band got underway in 1999 when Shahrokh Izadkhah and Babak Riahipour started mixing up lyrics from Hafez with acoustic guitar, bass, and Persian sehtar. After Ershad rebuffed their application for a record contract, they went underground and played for a mixed-gender audience in a concert held at a Russian Orthodox church in Tehran, an unprecedented move that won over fans then and since.

Norik Misakian

After their album and license for live performance were rejected by Ershad, the prog rock quartet Norik Misakian Band finally held their first live show in 2006 in a high school amphitheater in Tehran. As Iranians of Armenian descent, they cover classics by Pink Floyd, Yes, Deep Purple as well as their own charts composed by band leader Norik Misakian.

Hich Kas

The President of Iranian hiphop, Hich Kas dominates the scene as not only the pioneer of the latest generation of rap artists, but a singular voice against contemporary social issues facing youth in Tehran. His freestyle art can be discovered across the web in tracks like Manam Hamintor and Hichkas & Saatrap, and on Myspace.

Zed Bazi

Zed Bazi are Mehrad Hidden, Saman Willson, and Sohrab Mj – a rap trio originally from Tehran and now based in London – who cut sharp, controversial lyrics to the beats of hiphop artists like 50 cent and Dr. Dre. They maintain an independent presence through the internet through songs like Berim Fazaa and videos of their freestyle duo with Hich Kas.

Emziper

A major figure on Tehran’s scene, Emziper is a rap artist whose solo tracks like Khiyanat defy the current situation in Iran through sampled beats and kuche bazaar (Iranian street slang).

Shooary

Like other recent newcomers to Tehran’s rap scene, Shooary are influenced by rap pioneers Sandy (from Los Angeles) and Deev, whose Dasta Bala track was the first to set kuche bazaar to hiphop beats. Shooary add their own distinctive flavor to the underground rap scene through songs like Topo Bekan.

Iraq: Histories of Resistance

Baghdad: The Fertile Crescent of Classical Maqam

Renowned as a crucible for art music and scholarship in the Arab world, Baghdad was the historic crossroads for musical activity during the Abbasid dynasty (750-1258 AD). Vocalists and instrumentalists traveled to the Abbasid courts to study under preeminent masters and practice their arts in a cosmopolitan milieu that spawned the Baghdadi school of maqam. Contemporary Iraqi maqam is a cyclical song form that moves between fixed repertoire and improvised patterns of poetry and pitched sequences (maqamat) and incorporates instruments such  as santur, juza, and percussion (tabla, dunbuk, riq). Baghdad’s historical legacy spread to Cairo and Damascus during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and influenced the work of influential composers such as Said Darwish. Today’s top performers continue to express their debt to Iraqi luminaries such as the late Munir Bashir, whose legacy has been succeeded in part by his Cairo-based disciple, Naseer Shamma. One of Shamma’s most widely circulated compositions,“Happened at al-Amiriyya,” is a piece composed in response to the U.S. bombing of Iraq’s al-Amiriyya shelter in 1991, and is available on his Le Luth de Bagdad album.

as santur, juza, and percussion (tabla, dunbuk, riq). Baghdad’s historical legacy spread to Cairo and Damascus during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and influenced the work of influential composers such as Said Darwish. Today’s top performers continue to express their debt to Iraqi luminaries such as the late Munir Bashir, whose legacy has been succeeded in part by his Cairo-based disciple, Naseer Shamma. One of Shamma’s most widely circulated compositions,“Happened at al-Amiriyya,” is a piece composed in response to the U.S. bombing of Iraq’s al-Amiriyya shelter in 1991, and is available on his Le Luth de Bagdad album.

The political upheaval of the twentieth century severely impacted music making in Iraq. As an alternative to exclusively male coffeehouses in Baghdad, British occupying forces introduced cabarets and encouraged performances given by female singers for mixed audiences. The British occupation was denounced by regional praise songs such as the Bedouin “arda and aayla”, or war poetry, which have again become popular as a tool of resistance against the U.S. occupation of Iraq (see Sabah al-Jenabi below). During King Faisal’s reign from the 1930s to the 1958 anti-imperialist coup, external influences significantly altered the status of urban music in Iraq. Modern tarab compositions from Egypt and Syria influenced the work of renowned maqam vocalists Farida, Zakia George, Afifa Iskander, and Selima Murad. In contrast to these processes of modernization that pursued a pan-Arab nationalism through centralized radio and television, local singers of abuthiya gave voice to mawwal in Kurdish and other vernacular dialects.

When Iraqi Jewish musicians Saleh and Daoud al-Kuwaiti left for Israel in 1952, Baghdad suffered the loss of two of its major contributors to the arts. The al-Kuwaiti brothers not only established the official maqam ensemble of Baghdad Radio, they composed hundreds of popular tarab songs in collaboration with pan-Arab stars like Umm Kulthum and Mohammad Abd al-Wahhab and recorded regularly for cinema and radio. Contemporary cultural politics of the Arab-Israeli conflict continue to negotiate the work of these and other Iraqi Jewish artists in Baghdad in the extraordinarily fertile period of collaboration from the 1930s to the 1950s.

Umm Kulthum. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Censorship and Coercion under the Baath Regime

Following the Baath party’s coup of 1968, state institutions were established to preserve and encourage Iraqi music through recordings, collections, and training in performance and luthier craftsmanship. Nevertheless, classical maqam continued to decline due to migration from rural areas to cities, the growth of urbanization and literacy, and the general redistribution of wealth. These processes also contributed to the failed integration of Iraq’s disparate communities which led to, and merged with, the rise of Saddam Hussein. Ethnic minorities found it difficult to perform under these centralized efforts which cloaked the coercive policies by which the Ba’ath regime strategized Iraqi nationalism. The Baath party harassed, imprisoned, and tortured Sufi praise singers and Kurdish musicians, such as singer Newroz. Arrested in 1979 by the Baath party because of his incendiary lyrics laced with symbols of the Kurdish revolution, Newroz chose a life in exile and was eventually granted political asylum in Britain in 1989.

The Baath regime’s zero tolerance policy for dissent was enforced through the Hussein family’s control of Iraqi state media and cultural affairs. Pop singer Nizar al-Khaled recounts his experiences with the capricious Uday Hussein, who owned the main daily newspaper, Babel, as well as the youth and entertainment channel Shebab: “Me and another singer, Haitham Yousef, were really popular with the girls, so Uday stopped us appearing on television. Then last year [2002] they produced a list of singers who had not sung for Saddam yet [on TV], so I had to do it – twice. Yousef fled the country after Uday had a group of girls beat him up at a concert. And there are other incidents, like one in which Uday urinated on a singer because he didn’t like his looks.”

From Sanctions to Exile: Profiles of Contemporary Iraqi Artists

Following the 1991 Gulf War, U.N.-sponsored economic sanctions severely constrained conditions of music production in Iraq. Musicians departed for Jordan, Cairo, and other major Arab cities, so many that the government paid salaries to the remaining performers in order to cut the rate of emigration. The sanctions also severed access to imported music markets such as jazz, rock, funk, and alternative music. Local heros emerged in the face of this economic and cultural isolation, charismatic individuals like Alan of Alan’s Melody whose bootleg record shop in the Baghdadi neighborhood of A’arasat became a central hub for music lovers of all genres.

Despite this recession, a new generation of pop music singers emerged in the 1990s, some of whom are now among the most popular stars in the Arab world (see Kazem al-Saher below). In addition to amplifying traditional vocal aesthetics with electronics such as the keyboard and bass, this generation has appropriated global hip-hop and rock samples into Iraqi popular music. Rising pop stars include vocal artists like Abdullah Abdul Wahid, Wael Adel, Jamal Abdul Nasser, and Hummam Abdul Razzak.

Kazem al-Saher

One of the largest-grossing artists in the Arab world, Kazem al-Saher’s career began when he sold his bicycle for a guitar – an audacious gesture that has continued to characterize his career. His first major hit was censored by Iraqi authorities sensitive to the cultural politics of the Iran-Iraq war, an act which served only to increase the song’s popularity on the black market. After choosing a life in exile in Cairo (after a brief two-year stint in Lebanon), politics again jumpstarted his career. In 1995, at a moment when international media began to cover the consequences of U.N. Sanctions on Iraq, he performed Yidrib al-Hob on Egyptian TV and voiced solidarity with his fellow brethren. Thus his creative arrangements of Iraqi classical music and poetry, Arab pop, and more recently, Western opera and Algerian rai, are delivered with a politically acute sense of timing that continually brings Iraq to the center of the Arab world. Today, al-Saher continues to speak out against the U.S. occupation of Iraq through his music, especially the 2007 release “Al-Rowaa wal Nar” (Barbarians and Fire) and the spotlight of international media.

Iraq Today: The Violence of Virtue and Vice

Life as a musician in Iraq today is more unstable and risky than at any other moment in the history of modern Iraq. According to the Iraqi Artist’s Association (IAA), nearly 80 percent of the singers during Saddam’s era fled the country and at least seventy-five singers have been killed since the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. Active singers face threats from religious extremists and avoid public performances because of the security situation. Casualties of regime change have not overlooked singers, particularly those who were active under Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship. In an extreme case, the head of the Musicians’ Union, Dawoud al-Qaisi, was shot in May 2003 due to his affiliations with the Baath elite, an assassination that prompted many others to go into hiding. Other acts of violence include, for example, the bombing of music shops in the Summar district of Baghdad, students assaulted by armed members of al-Sadr’s movement for listening to music while at a picnic in 2005, and gunfire riddling music stores in Baghdad earlier this year.

While these acts of violence stem from complex and varied causes, many can be attributed to the religious authority of Islamic cleric Muqtada al-Sadr under which an Islamist interpretation of shari’a (Islamic law) is enforced on all practices of civilian life.

The Mehdi army of al-Sadr maintains a coercive presence and strict surveillance of many neighborhoods in Baghdad, and frequently close concert halls, clubs, and music stores. Washington Post journalist Sudarsan Raghavan reported in September 2006 that young Mehdi foot soldiers posted religious edicts in north-central Baghdad that banned vices like “music-filled parties and all kinds of singing, celebratory gunfire at weddings, the gathering of young men in front of markets or girls’ schools” and also suggested that men should cut their hair. The totalitarian presence by which these morals are enforced—literally the presence of al-Sadr’s men at girls’ school, at the market, and on main streets, as well as the feared home visit—produces an atmosphere of paranoia that immobilizes the human right of freedom of expression and has nearly destroyed local music industries in Baghdad.

“They wanna war for the rest of future

They said you don’t need it much longer

They wanna war and you wanna peace

And you know you got — got kill the beast.”

Singers Resist the US-led Sound Invasion on Iraq

In efforts to influence Iraqi popular sentiment through mass media, the US Army established radio and television stations that broadcast Western and Arab pop music. In response (and in violation of the ban against “any sort of public expression used in an institutionalized sense that would incite violence against the coalition or Iraqis”), Iraqi singers like Sabah al-Jenabi popularized praise songs that call for guerrilla war and extol the “men of Falluja for hard tasks” who will “fight the Americans like leaderless soldiers. We’ll drag Bush’s corpse through the dirt.” Sabah al-Jenabi’s popularity has soared not only among jihadists but also among the general Iraqi public for whom the jihad music can “make them feel good.” Other singers in this underground industry include Sayyed al-Hassooni and Abdul Rahman al-Refai.

Lebanon: Histories of Musical Resistance

Zajal: Dueling Wordplay

A contemporary vernacular practice of improvised oral poetry, zajal can be traced to ninth-century migrations between North Africa and the eastern shore of the Mediterranean. Performances of zajal are often staged as a competition of rhymes between two dueling wordsmiths, and are typically sung in two musical styles: free rhythm (nath al-naghamat) and metered rhythm (zazm al-naghamat), accompanied by daf, or tambourine. Each of the two poets in zajal performance recites the opening qasid and then address four topics based loosely on themes of love, nature, morality, and confessionalized eulogies. Well-known zajjaale who perform Lebanon today include Talih Hamdan, Zaghloul el-Damour, Moussa Zgheib, Asaad Said, and Khalil Rukoz.

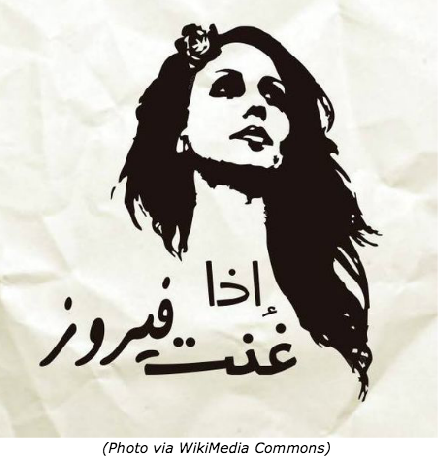

Fairouz: Voice of Lebanon

With a voice that embodies the soul of Lebanon, Fairouz is one of the best-known singing stars of the twentieth century. Born near a back alley of Beirut known as Zoqaq el-Blatt, Fairouz is beloved for the bell-like timbre of her voice, the sentimental nature of her lyrics, and the versatility of her career that fused European instrumentation and dance rhythms with Lebanese dabke (vernacular dance) melodies on stages across the world. In collaboration with her husband ‘Asi Rahbani and his brother, Mansur, Fairouz stirred nationalist passions in the period following the 1967 defeat by Israel with political songs such as “Zahrat al-mada’in” (“The flower of cities”), an ode to Jerusalem that laments its loss. Other songs committed to Palestinian nationalism include “Jaffa,” “Bisan,” “Sanarji’u Yawman” (“We will return one day”), “Raji’un” (“We are returning”), and “Jisr al-‘Awda” (Bridge of return).

With a voice that embodies the soul of Lebanon, Fairouz is one of the best-known singing stars of the twentieth century. Born near a back alley of Beirut known as Zoqaq el-Blatt, Fairouz is beloved for the bell-like timbre of her voice, the sentimental nature of her lyrics, and the versatility of her career that fused European instrumentation and dance rhythms with Lebanese dabke (vernacular dance) melodies on stages across the world. In collaboration with her husband ‘Asi Rahbani and his brother, Mansur, Fairouz stirred nationalist passions in the period following the 1967 defeat by Israel with political songs such as “Zahrat al-mada’in” (“The flower of cities”), an ode to Jerusalem that laments its loss. Other songs committed to Palestinian nationalism include “Jaffa,” “Bisan,” “Sanarji’u Yawman” (“We will return one day”), “Raji’un” (“We are returning”), and “Jisr al-‘Awda” (Bridge of return).

During the Lebanese civil war period (1975-1991), Fairouz maintained a pact of silence. Her refusal to sing was a tactic that evaded political appropriation of her live voice by hostile factions involved in the conflict. In 1994, she broke her silence with a controversial appearance at the Beirut Festival held in downtown Beirut.

In celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the Baalbeck Festival, Fairouz was scheduled to lead the Rahbani Brothers musical, “Sah el-Nom,” in a mid-July 2006 appearance that was abruptly sabotaged by the Israeli siege on Lebanon as bombing raids specifically targeted the surrounding town of Baalbeck.

On December 1-3, 2006, Fairouz yet again demonstrated her commitment and strength of renewal with a restaging of “Sah el-Nom”, which she performed to sold-out crowds in downtown Beirut at the BIEL center. A living testament of Lebanese resilience to destruction, her performance was invigorated by the Hezbollah demonstration that took place just moments away.

Marcel Khalife: Beloved Dissident

A self-made cultural phenomenon, Marcel Khalife gained popularity in the 1970s and 1980s for his songs of resistance to Israel’s occupation of southern Lebanon. He began as a protest musician who played in the American University of Beirut’s cafeteria and quickly gained a local following among students. Khalife is well-known for his settings of Mahmoud Darwish’s poems, such as the iconic “Ila Ummi” (“To my mother”) which speaks to nostalgic and traumatic conditions of Palestinian exile. Though many audiences maintain an allegiance to Khalife’s nationalist repertoire of songs, his songs also seek to reimagine musical form and instrumental timbre in ways that have provoked controversy.

Ziad Rahbani: Parables of Parody

Ziad Rahbani, the son of Fairouz and ‘Asi Rahbani, is regarded by many Lebanese artists as the visionary of the civil war generation. For example, this collection of recordings, taken from a radio station in West Beirut, offers wry commentary on the early period of the Lebanese civil war with an ingenious sense of humor and narrative. Though Ziad’s extensive oeuvre is inextricably influenced by his parents, and his continuing collaboration with his mother, his work expresses a deep ambivalence about the forms of intangible cultural heritage that his family has constructed for Lebanon, such as folkloric representations of the mountain village, or vernacular and classical music forms (‘ataba, tarab). Of his plays, musicals, and compositions that parody these themes, Ziad Rahbani’s 1983 production, A Failure, is a highly critical play within a play that opposes war and conflict by sketching the difficulties of theater production during times of war. Today, Ziad directs, arranges, and composes for Fairouz (see “Sah el-Nom”), among other projects.

Ziad Rahbani, the son of Fairouz and ‘Asi Rahbani, is regarded by many Lebanese artists as the visionary of the civil war generation. For example, this collection of recordings, taken from a radio station in West Beirut, offers wry commentary on the early period of the Lebanese civil war with an ingenious sense of humor and narrative. Though Ziad’s extensive oeuvre is inextricably influenced by his parents, and his continuing collaboration with his mother, his work expresses a deep ambivalence about the forms of intangible cultural heritage that his family has constructed for Lebanon, such as folkloric representations of the mountain village, or vernacular and classical music forms (‘ataba, tarab). Of his plays, musicals, and compositions that parody these themes, Ziad Rahbani’s 1983 production, A Failure, is a highly critical play within a play that opposes war and conflict by sketching the difficulties of theater production during times of war. Today, Ziad directs, arranges, and composes for Fairouz (see “Sah el-Nom”), among other projects.

Emerging Voices of Resistance: Responses to the 2006 War With Israel

“From Beirut…to thase who love us” (July 2006)

This video was produced by a consortium of artists, including vocalist Rima Khcheich, during the first days of life under siege.

“We Live…” (July 2006)

A live benefit concert recorded in Kuwait and mastered in Beirut that affirms music as an immediate response to chaos, isolation, paralysis, crisis—in short, military siege. Producer Ghazi Abdel Baki (Forward Productions) gathered with poet Meshal Kandari and musician friends Charbel Rouhana, Abboud Saadi, and Ziyad Sahhab at the legendary Blue Note Cafe in West Beirut during the first week of siege. This album is the result of their collaborative commitment to a Lebanese way of life. Proceeds will benefit local relief efforts in Lebanon.

“Qana” (August 2006)

US-based rocker Patti Smith created this heartbroken response to Israel’s July 30 attack on Qana.

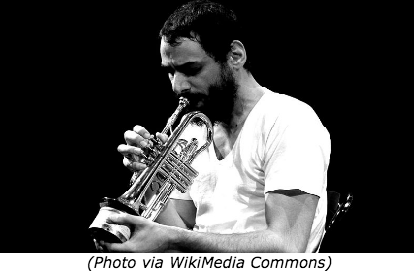

Mazen Kerbaj

Mazen Kerbaj jumpstarted Irtijal, the hub of Beirut’s free improvisation scene, in 2000 with Christine and Sharif Sehnaoui, and Raed Yassin.

His work, in comics and illustration as well as music, defies convention. On the fourth day of Israel’s 2006 siege, Mazen began blogging drawings which interpreted the ambiguities and anxieties of war with startling clarity, coherence, and immediacy. His ongoing work continues to distill the visceral experience of modern life in Beirut.

His work, in comics and illustration as well as music, defies convention. On the fourth day of Israel’s 2006 siege, Mazen began blogging drawings which interpreted the ambiguities and anxieties of war with startling clarity, coherence, and immediacy. His ongoing work continues to distill the visceral experience of modern life in Beirut.

During the war with Israel, Mazen frequently placed an MD recorder on his balcony in East Beirut and performed duets with the live sounds of bombs. By staking the creative individual against anonymous forces of mass destruction, Mazen’s act of subversion reclaimed his starry nights from the powerlessness of life under siege-“Starry Night” circulated widely during the war.

The Grendizer Trio, which features Mazen, Raed Yassin and a rotating cast of other musicians, took this idea a step further with their mid-October show that presented the duo in performance with “July’s War”.

Julia Boutros

Pop singer Julia Boutros initiated a fundraising project, Ahibaii, that donates the proceeds of her November 2006 tour to families of those martyred during the July war. The project is named after a chart-breaking single that sets to music a letter written by Sheikh Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah to Hezbollah fighters in August 2006. This project is the latest development in Boutros’ longterm commitment to Lebanese nationalism.

The Lebanese Underground

An informal network of Beirut-based musicians, artists, and activists who work, record, and play together. Here are some of their recent antiwar productions:

- Musicians AGAINST Monsters Concert (Beirut)

Local indie scene fixtures Scrambled Eggs (Charbel Harber) and The New Government produced a benefit concert at Club Sociale during the 2006 war with all proceeds sent to Samidoun, a locally-based Lebanese relief organization. - Kill War Concerts (Amman)

UTN1 (Baghdad) joined with Beirut-based rap artist RGB, Sisska (Kita3 Beirut), and DJ CTRL+Z (Beirut) for the first fundraising concert in August at Blue Fig. A second concert featured DJ Lethal Skillz (Beirut) and DJ Sotusura (Amman).

From Berlin to Beirut

DJ Jade of Basement (and formerly of Blend, see below) organized this fundraiser for charity organization Mowatinun at Watergate in Berlin.

Blend

Though no longer active, alternative rock ensemble Blend produced their debut album, Act One (2003), as a response to the civil-war period and violent social aggression.

The Kordz

Mixing rock aesthetics with politically sensitive lyrics, The Kordz are a Beirut-based band that devoted a concert to charity work in South Lebanon.

Hezbollah: Music as Resistance Tactic

Hezbollah has declared its resistance to the violation of Lebanese airspace by Israel, as well as its commitment to liberating Lebanese land from illegal Israeli occupation. Whether or not the use of violence is justified for resistance purposes, a question that emerged after WWII with respect to decolonization processes, muqawama (resistance) is a defensible platform that shapes Hezbollah’s main objectives and strategies. In order to build broad-based support for its ongoing campaigns, Hezbollah maintains public relations and media departments, produces television and radio programs, and regularly demonstrates in Beirut, South Lebanon, and the Beqaa Valley.

Music is an integral component to these strategies of resistance. Comparable to other forms of militant mobilization, songs help inspire allegiance to Hezbollah through march tempos and lyrics that are usually sung in a deep bass register by a men’s chorus. Hezbollah maintains a military band, which played to demonstrators in the December 2006 protest against Lebanese PM Fouad Siniora and was featured by the NPR program The World. Music videos are also regularly produced by Hezbollah.

Palestine: Histories of Musical Resistance

Iltizam: (Commitment) through song

Cultural resistance has been synonymous with Palestinian music and song since the forcible expulsion of Palestinian Arabs from their villages in 1948, a series of events that is referred to as the nakba, or catastrophe. For many composers and singers in the greater Arab world, especially those working in the cultural mecca of Cairo, the Palestinian crisis has and continues to figure in their work as a symbol of the struggle to establish political sovereignty and the commitment to creating modern forms of Arab culture that are distinct from Western influence. Of the many artists who have evoked Palestine through the power of song, the Egyptian composer Mohammad Abd al-Wahhab marked the first major attempt to align Arab unity and nationalism with the liberation of Palestine through his “Filastin” (1949).

Another important Egyptian figure was Sheikh Imam ‘Isa, a blind dissident whose work circulated widely among underground circles of Arab intelligentsia, fueled a revolutionary spirit in solidarity with Palestinian guerrillas, and landed him in jail under both Egyptian presidents Nasser and Sadat. His “Ya Falastiniyyeh” (1968) is still beloved for its position of sympathy and solidarity with Yasser Arafat’s then-nascent PLO. An indicator of how music can be used as a weapon of resistance, Arafat reputedly insisted on meeting Sheikh Imam during his visit to Cairo in August 1968 and requested a performance of the song:

O Palestinians, I want to come and be with you, weapons in hand

And I want my hands to go down with yours to smash the snake’s head

And then Hulagu’s law will dieO Palestinians, exile has lasted so long

That the desert is moaning from the refugees and the victims

And the land remains nostalgic for the peasants who watered it

Revolution is the goal, and victory shall be your first step

After 1967, a genre of political songs were produced by Palestinian diaspora musicians, such as al-Firqah al-Markaziyya and Abu ‘Arab in Lebanon, that conveyed collective loss and rupture. These revolutionary songs took up Palestinian forms of improvised poetry, known as mawwal, ‘ataba, or mijana, to express outrage and grief at the razing and appropriation of Palestinian villages by Israelis. In the 1970s and 1980s, Lebanese singer Marcel Khalife set to musical composition the early works of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish in ways that evoked the everyday struggle for a Palestinian national identity, for example, the song “Jawaaz al-Safer” (“Passport”) in his 1976 album “Promises of the Storm.”

In the 1970s and 1980s, due to Israeli authorities that viewed music as a propaganda weapon of resistance, active Palestinian musicians worked under the constant threat of arrest and censorship. Their work was marginalized by the censorship of Palestinian nationalist lyrics in the Israeli broadcasting industry. Moreover, cassette tapes were frequently confiscated by Israeli security in border checks, in addition to personal belongings. Many artists, such as singers Suhail Khoury and Mustafa al-Kurd became more popular after their arrest or confiscation of their work.

Musical resistance during the first Intifada (1987-1993) was practiced through both the abstinence of music and emerging directions in Palestinian music. For many living in the occupied West Bank and Gaza during the Intifada, musical performance was an expression of joy that violated the experience of living conditions under occupation and the everyday losses of militant resistance. To refrain from playing instruments or cassette tapes was a gesture of respect in honor of those who were martyred. In this same period, one of the most influential groups in Palestinian cultural history was founded in Ramallah. Since the early 1980s, Sabreen has sought to represent the Palestinian struggle in avant-garde compositions that adapt Western and Arabic instruments to the themes of land and its fertility, romance, and dreams. Examples include their 1980s album “‘An As-Sumud” and “Ala Fein.” Sabreen continues today as a non-profit association for Palestinian culture, while the group’s lead singer, Kamilya Jubran, departed in 2002 for a solo career that continues to explore processes of modernity in Arab song and voice. Her album Wameedd (2005) is a particularly haunting experiment in trip-hop and tarab vocals.

Other prominent artists who emerged in the first Intifada and expanded their work during the peace process of the 1990s include Amal Murkus, who, like many others, has been strongly influenced by Marcel Khalife, as well as Rim Banna, Nawa, Baladna, al-‘Ashiqeen, Firqat al-Fanun al-Sha’biyyah, Issa Boulos, and Trio Joubran.

Lullabies and Children’s Songs

In addition to those artists who are popular among audiences outside of Palestine, certain figures continue to grace the local landscape of Palestinian song, particularly lullabies. Um (“mother”) Jawaher Shofani is a grandmother beloved for her singing of traditional songs at weddings, funerals, circumcisions, and baptisms. She is featured on an album, Lullabies from the Axis of Evil, that is available in the US.

A 2004 film production on the conditions of occupation in the Balata refugee camp near Nablus, “The Sun Doesn’t Shine in the Camp” features several songs recorded by children.

Palestinian Hip Hop and al-Aqsa Intifada

Any history of al-Aqsa Intifada must include the story of Palestinian hip-hop, which began in 1998 with the Nafar brothers and is now one of the main modes of cultural resistance in Palestine and the Arab diaspora. Though the rise of Palestinian hip-hop corresponds with the collapse of the peace process, Palestinian rap artists confront not only the ongoing Israeli occupation but social issues in Palestine, such as drugs, crime, hypocrisy of Arab governments, commercial corruption of music, and the crisis of being caught between (at least) two cultures. Those in the West Bank and Gaza hip-hop scenes bear an uneasy relationship with Islamists, especially those affiliated with Hamas, who may censor—sometimes violently—hip-hop concerts. When considered loud and morally suspect celebrations, these concerts violate a code of conduct that respects the duress of hostilities during the second Intifada. Palestinian hip-hop artists are not isolated from their Jewish rap brethren in Israel—various festivals and documentaries, such as Anat Halachmi’s Channels of Rage, present the politics, influences, and collaborations among rap artists in Israel and Palestine.

Slingshot Hip Hop

Detroit-based filmmaker Jackie Salloum’s documentary film frames the artistic work and personal lives of Palestinian hip hop crews in Gaza, the West Bank, and inside Israel. It aims to spotlight alternative voices of resistance within the Palestinian struggle and explore the role their music plays within their social, political and personal lives. The film’s trailer and website are portals to Palestine’s contemporary hip-hop scene. A hip-hop group based in the United States, The Philistines, released a compilation CD “Free the P”, the proceeds of which support the film project and Palestinian hip-hop more generally.

DAM

Palestinian hip-hop group DAM seeded a scene with an attitude that it’s “not just hip-hop, it’s living two cultures…it’s mixing our Palestinian culture, our Arab culture, with our situation living among the Jews as a minority culture and with American hip-hop,” says Tamer Nafar. He started rapping in 1998 with his brother, Suheil, and joined with Mahmoud Jreri to form the leading Palestinian hip-hop crew. DAM—which is Arabic for eternity, means blood in Hebrew, and is an acronym for Da Arab MC’s in English—takes musical influences from Arabic pop and urban American hip-hop (e.g. Public Enemy) and raps in Palestinian Arabic, Hebrew, and some English. Through political songs such as “Min Irhabi” (“Who’s a Terrorist?” 2001), DAM voices the common experience of Palestinians in provocative and confrontational lyrics:

“You call me the terrorist?

Who’s the terrorist?

I’m the terrorist?

How am I the terrorist

When you’ve taken my land?!

Who’s the terrorist?

You’re the terrorist!

You’ve taken everything I own

while I’m living in my homeland.”

(full lyrics)

PR – Palestinian Rappers

“I am Palestinian…

I live like a prisoner, estranged in my own land during this time

For your sake Palestine, our screams have been silenced

Our words have been denied

Our movement has been paralysed.”

R.F.M.

Also based in Gaza, R.F.M. is a rap trio that reaches out to youth and critiques those Palestinians who ignore the social problems in their society. Their message is critical, uncensored, and confrontational, but it has generated an appeal to multiple generations and audiences. Below are the lyrics to what some call their most controversial song, “Watch Your Back, Arabs,” which addresses both Israelis and Arabs:

“Where are the Arab people?

Where is the Arab blood?

Where is the Arab anger?

Where, where and where …

Driving the coupe car

Smoking the cigar

Voting for the super star “American Idol”

And forgetting about our martyrs, wounded, prisoners…Have you heard the last news!?”

[Featured image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.]